I remember when I was nearing my graduation from college. I was 22 years old. Other than partying, all anyone was thinking about was what the heck they were going to do with their lives.

“What should I do next?”

“Should I get this job? Should I get that job? Should I get any job? Should I start my own business? Should I get my MBA?”

They’d ask friends, parents, professors, and anyone else they viewed as someone who might have the answer for them, hoping they could pass down some nugget of wisdom that would make everything clear for them. They wanted to be successful. They wanted to make a lot of money.

There was one problem: they were asking the wrong people.

The majority of these people think in a way that is -EV(negative expected value), so most people are getting advice in spots like this from sources who while trying to help them, don’t think in a logical way that will lead to the +EV route(positive expected value). They think in a way that can be summed up as “avoid risk at all costs.” Most of their advice will come from this angle. They don’t realize their rationale for decision making comes from there, but it’s how most people are brought up, so it’s not unnatural to think in the way that leads to the least amount of variance. A byproduct of attempting to avoid variance in the decision making process means avoiding +EV choices.

Most people don’t think in terms of EV, and it’s costing them a lot of money.

If you’re not familiar with expected value, you’re probably asking, “okay, what is it, and how can I use it to make more money?”. Even people who are familiar with EV have sent me emails asking how they can apply it to business to make more profitable decisions.

The goal of this post is to help you think about how to use EV to easily make the correct decision. Situations that used to seem difficult to make should become much clearer. Deals that you never would have looked at in the past because they seemed “risky”, may have been great opportunities that you won’t miss again in the future. All of this leads to a much more profitable future for you. If you can correctly understand EV, and apply it to all of your financial decisions, you will make substantially more money.

So, what is expected value?

The definition of expected value is: the sum of all possible values for a random variable, each value multiplied by its probability of occurrence.

“Great, but how can I make more money with it?”

I’m going to explain with some examples.

The simplest example of EV would be flipping a coin. You and a friend bet each other $1. You pick heads, your friend picks tails. The winner takes the $2. Since each of you has a 50% chance of winning, your EV is $1. Since you’re risking $1, there is no edge on that bet. It’s neutral EV.

—

Let’s do a simple example from poker. I think the way edges are taken in poker is a good segue to how the same can be applied to business (if you don’t understand the basics of poker, just skip to the next example):

I played poker professionally for several years. I was a very aggressive player. Many amateurs look at poker as a game of luck, because they don’t understand where the edges come from. Pushing these small edges (or +EV spots) over and over is what enables good players to make a very good income. Here’s a very simple example of a situation that would be +EV that most professional poker players would make, and many amateurs wouldn’t, and wouldn’t understand why the pros were doing it (again, skip this example if you don’t understand the basics of poker).

Let’s pretend there is $30 in the pot after I raise pre-flop and only 1 player calls. The flop comes, and I don’t have anything. My opponent checks to me. I bet $15.

“But why would you bet if you didn’t have anything?”

Simple, I’d bet here if I thought it was +EV. I’m risking $15 to win $30. If I think my opponent is going to fold more than 1/3rd of the time, then I should bet(because for every 3 times you bet you only have to win once to break even). If I think he would fold less than that, I shouldn’t bet $15.

Most amateurs’ thought process if they were told they should bet would be: “ya, but what if he has something?”, “I don’t have anything”, “what if he calls my bluff?”, or “I don’t want to risk it”. These questions are irrelevant to what makes the play +EV or not. If based on the player/situation, you feel he would fold greater than 1/3rd of the time, it is correct to bet.

Most amateurs would pass up that spot to bet. Most professionals would not.

Let’s pretend based on that player/hand example that the player would fold 40% of the time. Let’s pretend you’d lose the hand 100% of the time he calls (you wouldn’t, but again we’re keeping the example simple). Assuming these things, here is what would happen:

60% of the time, you’d lose $15.

40% of the time, you’d win $30.

60% x ($15) = ($9)

40% x $30 = $12

($9) + $12 = $3

EV = +$3

Your EV is $3, because that’s your expected profit from making that bet. Whether you lose on this one individual hand is irrelevant. You make $3 in EV. Over the long run, all of the +EV spots add up. A LOT.

Note: for people reading this without much of a background in poker or EV, you don’t add the money already in the pot to your loss if you lose the pot, because it’s already in the pot regardless of whether you win or lose the pot. Each situation itself is it’s own EV calculation. It doesn’t matter what happened in the past. You want to choose the +EV route as many times as possible. Don’t let the past dictate your thought process on making the correct decision.

Most amateurs would have passed up the $3 in EV on that hand because they wouldn’t have known it was a +EV play.

Professionals on the other hand will put themselves in thousands of situations where they can squeeze a little extra EV out of their opponents. Because it’s hard for amateurs to understand why they’re making the plays they’re making, they don’t realize the pros are making mathematically correct plays, despite seeming lucky to the untrained eye.

“Oh, he’s just lucky I didn’t have anything there. He’s betting all the time, he must be getting great cards. Just wait until I get some cards!”

While the amateur is “waiting for cards”, the professional is picking up free money in all the spots the amateur doesn’t have anything. He can, and should, because it’s +EV to do so. In the short term, he might win or lose using this aggressive strategy. In the long term, someone consistently making +EV plays is going to make all the money. It’s mathematically impossible for them not to.

Someone that is trying not to lose money, avoids spots that might seem risky. Someone who wants to make money, explores opportunities that may be +EV. Play to win, don’t play not to lose. Playing not to lose actually increases the chance that you will lose.

—

This is a good segue into thinking about how EV can be applied to making money in business.

Before I get into the examples, it’s important to remember that if you have a crappy product or service you’re planning on offering, it’s going to make it much harder to correctly calculate the EV. To help you understand how to avoid this, read this post if you haven’t already: https://foreverjobless.com/how-to-create-a-business-that-prints-money/.

Your goal should be to make your business better than what’s currently out there and/or fill a gap in the market. Making projections with a business like that makes it 100x easier than if you were to throw a random business up like most other people do. Then, just figure out how you will reach your market.

“How many people will buy my crappy product/service” = impossible to calculate. If you’re planning on launching a business that sucks, trying to calculate the EV is a waste of time.

Many +EV spots seem risky at first glance, and that’s a big reason why they’re +EV in the first place. Most people are avoiding these opportunities, which often means the price for some of them is lower than it should be because so many people are afraid of short term variance.

Expected Value for Business

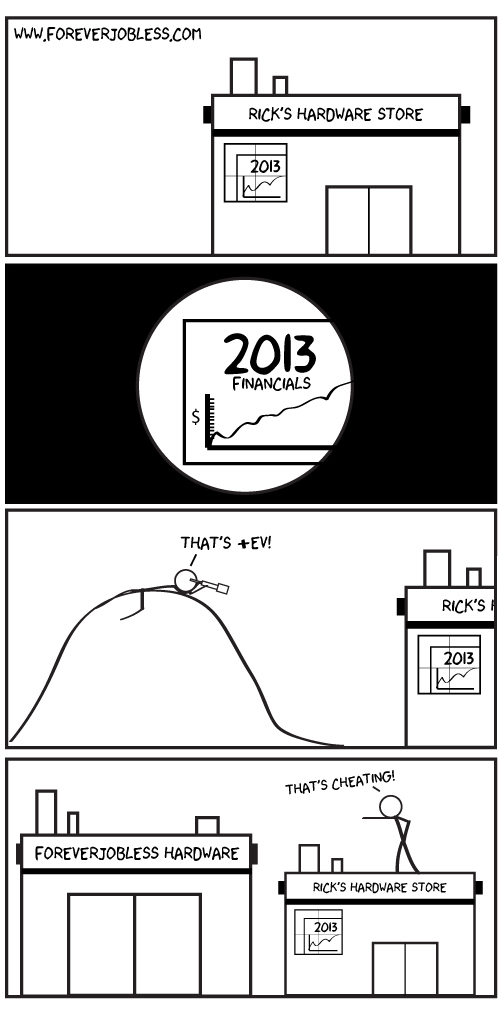

Here’s an excerpt from this post (https://foreverjobless.com/how-to-buy-a-ferrari-for-20k/) where I was evaluating purchasing a store that made $900/month for $4k. A quick EV calculation proved it was a no brainer to purchase (so obvious you wouldn’t need to do any math). Being able to quickly decide if it was +EV allowed me to get the deal before anyone else, because they were spending time mulling over the potential risks:

The first store that I purchased last year was for $4,000. Within the first 4-5 months I had already made my money back on the store. Since the purchase, I’ve made over $15,000 from that one store.

I can remember looking into it and figuring something must be wrong if they were willing to sell for that low. “They must be trying to rip people off.” Or, “there must be some sort of a catch” is usually the first thought that goes through your head when things seem too good to be true. However, that’s usually what stops other people from doing the research necessary to determine if something IS off, or if it’s just a good deal that other people have passed over because of incorrect assumptions.

I decided, what was the worst that could happen? I lose $4k. What’s the best that can happen? I have a site that kicks off $10,000+ per year relatively passive, and I learn a bit about e-commerce stores to see if that’s something I wouldn’t mind doing. I did my due diligence, and it seemed like a good bet to make, so I made it. Even if it hadn’t worked out, was it the wrong decision?

Even if there was some catch I missed, and I lost everything on the deal 50% of the time, that deal is still very profitable.

50%: -$4k

50%: +10kEV = +$3k

The simple math would tell you that even in this horrible case scenario, the first year your EV would be +$3k. That’s only IF you were going to lose all your money 50% of the time, which isn’t going to happen.

This calculation is also not factoring in that when you don’t get ripped off, the site is still making you money long term, and you still have an asset. So this decision should be a no-brainer, yet most people decided not to buy it because it “seemed too good to be true.”

It’s important not to be results oriented in business. Even if I lost money on this deal, it was the right decision to pull the trigger. It has very little to do with the end result of the investment, and mostly everything to do with the decisions that led you to that result. The final outcome is usually irrelevant. In the long term, everything works itself out if you are putting the work in and consistently making +EV decisions.

Don’t let emotion get in the way of making money. Some simple math will tell you everything you need to know, and it’s often going to lead you in a different direction than your initial emotional response would have.

Most people’s emotional response to that deal was “risky” because there was a good chance something was wrong if it was selling for that cheap. A quick EV calculation showed that it was +EV. Since I was focused on the EV instead of the risk, I bought the deal. Most others inquiring about the deal will never know they missed out on an extremely +EV deal. That one deal isn’t going to change the course of their financial future. However, what if they have 1,000 opportunities in their lifetime where they are passing up almost every +EV opportunity they come across just because they could potentially lose? That’s the way most people play the game, and it’s obviously costing them a ton of money.

—

In this post (https://foreverjobless.com/update-foreverjobless-is-back/) there was an EV example of why spending $84,000 on buying 4,000 books was +EV. My friend Jayson did the deal, and is living proof that it’s very profitable to make +EV decisions. He could have easily avoided the risk that came with spending $84k. Everyone else did. However, he decided to make the deal happen, and used that deal to help leverage the launch of an awesome company. He’ll make his $84k back many times over.

Maybe you’re saying to yourself, “well, I don’t have $84k laying around so even if I wanted to do a deal like that I couldn’t.”

Let’s take a look at some deals you could calculate EV on that wouldn’t cost much money at all to start:

Starting an e-commerce store, for example, is relatively easy to calculate an estimated EV for.

One good way is that you can check sites that are for sale, or that have sold. You can see how much they were making, and evaluate how they were generating their profits.

Was it from SEO?

From which terms?

Could you rank as well as they do for these terms?

If so, roughly how much would it cost you to rank?

Do you notice flaws on their site that would negatively affect conversions?

Calculate that into your EV with that niche.

Could you negotiate a bigger margin from the suppliers?

There’s a ton of things that you could factor into your EV calculation. Just depends how detailed you want to get. Knowing what people in that space are making is a great starting point to be able to calculate EV. It’s so easy it almost feels like cheating.

Don’t want to get too detailed?— you don’t have to make it harder than it has to be. Simplify it:

A business makes X amount of money. Can you do the same, or better than they did with that business?

If so, you can give yourself a very quick idea of what that business will make if you were to launch it. You can then attach a number to that business to give you a rough idea of what the EV is from the different options you’re choosing between. Make a list of as many of them as you want. Then, take the ones with the highest EV and take a deeper look.

—

If you don’t know what competitors in the market are making, that’s no problem. You won’t with most of them.

If I’m thinking of starting a store in a certain niche, I break down my estimated EV like this:

I multiply the amount of exact searches times the % of traffic each spot receives (see the Google Math graphic from example 2 in this post: https://foreverjobless.com/how-to-get-lucky-in-e-commerce/), times the spot I think I can get it to rank, and then I come to a number. Then I calculate estimated conversion. Then I factor in the margins.

Note: again in this example, you can be as detailed or as rough as you want. I can consult with SEOs to determine how difficult it’s going to be to rank for certain keywords, or I can make a rough guess by myself. I can calculate the rough traffic on 10 main keywords, or 100 keywords. All depends how thorough you want to be. Obviously the further you dig into each one, the more accurate your EV estimate will be, but it all depends where the best use of your time is. You can crunch numbers all day, but at some point you’ll need to pull the trigger or it’s pointless.

It’s simple:

Traffic x Conversions x Margins = Profit

—

So, if I have a niche where I think I can get roughly 3,000 hits/month based on where I think I can rank the keywords I’ll be targeting, and the estimated margins are around $50/sale, assuming I convert around 1%, I can expect that business to make roughly $1,500/month. Would $1,500/month on your business make you happy? If not, no biggie, move on to the next one. Better to figure out the rough EV on it now, than to launch it and spend a year only to find out it’s not making anywhere near what your goals are.

Note: I’m not saying EV solves everything for you. There are plenty of niches that are substantially more profitable than their EV will show at a quick numbers glance. It’s just meant to give you a good starting point to get you involved in opportunities that are closer to the range you’d like to be in.

Once you have a specific number to work with, you have something to compare to.

“So, if I was trying to decide whether I should work a job or start a business, could I use EV to help me?”

Absolutely— it’s a perfect spot to use EV.

—

If I was debating getting a job, or starting a store, I could look at the salary offered at a job, and compare it to the EV of starting a store. Most people wouldn’t do this, so they aren’t able to make +EV decisions… they just guess.

Most people would think about the option of getting a job vs. starting a store like this: “well, if I get the job I’ll make $50k (theoretical number), but if I start a store I could maybe make more, but I could also make less too, and that’s risky.” That’s a ridiculous thought process, but that’s really how people think. This way of thinking doesn’t help them come to any decisions that allow them a chance to be +EV over the long run.

The way I’d compare them would be: “well, if I get the job I’ll make $50k, but if I start a store my EV is $74k (theoretical), based on the estimated earnings plus the estimated asset value, calculated at a conservative multiple. If the store doesn’t go well, I have X amount of money put away to cover expenses that would enable me to live okay for X months until I’d need to find a job if it went horrible with the store. I could also extend the time by selling the asset I created. Therefore, I know I should start the store.”

That’s the amazing thing– you can always revert back to the -EV option if the +EV option doesn’t work out the first time. There are plenty of jobs out there. Most people choose the -EV option first, and think maybe someday they’ll get the courage to “take their shot.”

There’s rarely going to be a 100% fail safe plan.

‘If you wait for all the lights to turn green before starting your journey, you’ll never leave the driveway.’- Zig Ziglar

You need to take advantage of all the +EV opportunities you can. The sooner you do, the further along you’ll be when the next opportunity comes. If you never take them, you’ll be stuck in the same spot years later. Whether you take them now, or you take them 5 years from now, there’s always plenty of +EV business opportunities. The only difference is, if you start taking advantage of them now, in 5 years from now the EV calculations you’ll be making will have several more zeroes on them, because the +EV decisions you make now will have you in a very different spot financially than if you had passed them all up.

Most people would dismiss making a +EV decision before they even calculated what they were comparing. They would see risk, and turn away from that option. However, it’s obviously a lot riskier to consistently choose the -EV route.

If you choose to pass up +EV opportunities, you’re basically consistently making -EV financial choices. That’s the way 99%+ of people live though.

Think about it.

—

Here’s an example from one of my e-commerce stores where EV was calculated to determine if we should take a “risky” order.

A customer placed a large order, for over $5,000. They asked for 30 day terms on the order, meaning, they wanted us to send them the items and they have 30 days to pay us for them. We’d never given anyone terms before— we’d been asked, but we usually sell to individuals, not businesses. This was a big order, so it meant a nice profit. However, it also meant that we could lose a good amount of money if it was a scam.

My employee asked me what to do.

I asked him to look up some details on the business and let me know if he thought they were legit.

When we talked again, he told me they seemed like it. Based on what he told me, I thought that they were. We were getting somewhere around a 25% margin on the order.

I asked him, “based on what you know of them, do you feel like they’ll pay us greater than 80% of the time?” He did.

“Then do it”, I said.

I think he seemed a little surprised that it was that simple of a decision. It really was though. It’s just math.

Others may have passed up over $1,000 in profit on that deal since the customer could rip them off.

$5,000+ order

25% margin = $1,250

If we pretend they don’t pay 20% of the time, we’d lose roughly $3,750 those times.

So, here’s the math:

20% x ($3,750) = ($750)

80% x $1,250 = $1,000

Minimum of $250 EV in the deal.

Keep in mind, that’s using very conservative math. I didn’t think they were going to rip us off 20% of the time. I just used that as a bad case number where I would still obviously need to do the deal. If you get a +EV number using conservative math and still don’t pull the trigger, you’re leaving a lot of money on the table.

This is just one example from a day of running e-commerce stores. It was +EV opportunity that some others would have passed up. There are +EV situations everyday that you come across and are probably passing up at the moment because of the perceived “risk”.

Think logically, not emotionally.

—

Let’s take a look at an example that’s a little outside the box.

Take a look at this video:

A few years ago, this guy bought 70 domain names with combinations of potential presidential and vice presidential candidates. One of them ended up being romneyryan.com, which was the correct combo for the Republican Party. It’s easy to say, “oh, he was lucky that’s just gambling.” That’s not an inaccurate statement. It is a gamble, and it’s lucky to get the one that turns out to be correct. However, there’s a good chance it was a +EV investment. Even if situations like this don’t turn out to be +EV after breaking down the math, it’s important to evaluate them to expand your mind to think of other unique opportunities no one is thinking about. They aren’t thinking about them because they don’t consider the math. They think, “risk” and “gamble”, instead of EV.

Normally there are going to be X amount of potential presidential candidates for each party. It’s not like there are hundreds of people who could be our next president 1-2 years out from the next election. There’s usually a handful of frontrunners, and then a few rising stars in the party who may be considered. I don’t follow politics closely enough to give an accurate guess for what X would be on average, but it’s safe to say it’s relatively small. Obviously the number of potential vice presidential candidates is going to be much bigger. However, there’s a good chance someone who follows politics closely could narrow the range down to where it would be +EV.

This guy spent $720 on purchasing the domains, and their holding costs. His highest public offer through the auction was $8,050:

It’s a good assumption that he sold for at least that much, and possibly more after the auction ended and it didn’t hit the reserve he wanted.

To be on the conservative side, we’ll use the high bid as the number a potential domain would be worth.

If we say you’d need to spend $720 to buy 70 combinations, he could have bought roughly 783 combinations and still broken even if the price was $8,050. So, if we think there’s going to be less than 783 possible combinations, it’s going to be a +EV investment. (note: obviously some combinations will have a higher chance, so you could run deeper math— just keeping it simple for the example)

So, if someone thinks there are about 400 combinations of candidates, you can expect to roughly double your money on the investment in the long term.

“Wait, but doesn’t it matter how many I buy?

The more domains you buy, the higher your chances of picking the correct combination will be. If just for this example we pretend each combination has the same chance of being selected, than each extra domain you buy has the same EV. So, you’re going to risk more money the more domains you buy, but if you viewed it as +EV, the more domains you buy the better. Example:

If the average domain is costing $10.28, and you only buy 1 domain, you only risk $10.28. If you pick correctly, you make $8,050. We’ll pretend just for this example that you expect 400 potential combinations. This is how the math would break down in that scenario:

Investment: $10.28

Potential payoff: $8,050

Chance of payoff: 1/400 or .25%

.25% x $8,050 = $20.125

$20.13 – $10.28 = $9.845

Total EV = +$9.85

Divided by 1 domain = $9.85EV per domain

The guy from our example bought 70 domains:

Investment: $720

Potential payoff: $8,050

Chance of payoff: 70/400

17.5% x $8,050 = $1,408.75

$1,408.75 – $720 = $688.75

EV = +$688.75

Divided by 70 domains = $9.84EV per domain (same as above, just different by 1 cent because of rounding)

You’d expect to make $688.75 on your $720 investment over the longrun. (keep in mind we just used 400 combinations as an example)

So you can clearly see the more combinations you buy, the higher your risk would be, but your EV would also be higher.

This is a very high variance investment. This means if you were to make this type of investment one time, you’re probably not going to make money on that one investment. However, if you made investments like this many times, the variance would even out and you would make your money.

“So, should I do anything that’s +EV no matter what?”

No, I’m not saying that.

On high variance investments you just need to determine how much you’re willing to risk.

Example: if your entire net worth was $720, it’d be a bad idea to invest it all into a high variance investment like this, despite being +EV.

—

Another great example of this is health insurance. It’s -EV to have health insurance from a financial perspective, but because one bad accident could financially ruin you, it’s probably a good idea to have health insurance. If nothing else, for peace of mind. Insurance companies are in business because the policies they write are +EV for them. That’s how they make their money.

Personally, I have health insurance, but not dental insurance. Why? Because dental insurance is -EV, and I can afford the cost if something bad were to happen to my teeth. I’m not saying you shouldn’t have dental insurance, I’m saying if you have some money put away, it makes sense to at least calculate the numbers.

You want to see not only how many +EV opportunities you can take advantage of, but how many -EV situations you can avoid.

I’ve already given a number of examples, but I’ll give a few more because I think it’s important EV get ingrained into your mind when making decisions. There are so many no-brainer decisions that a lot of people pick the opposite way because they’re not thinking in terms of EV.

One popular one is, “I want to go to this conference, but I don’t know if I want to spend the money.” Whether you want to spend the money or not is irrelevant. Is it +EV compared to other things you could use the money for, or not? If it is, go. If it’s not, don’t.

I’ve always considered writing a book. A couple years ago there was a conference around writing/publishing Tim Ferriss ran that cost $7k to attend. I remember debating if I should attend. I mean, I didn’t even know if I was even going to write a book. So, I just assumed there was a 50% chance I’d end up writing the book. So, if I ended up writing the book, I had to decide if I thought I’d get $14k worth of value. If I self published I think I assumed I could make around $7/book, so I just had to decide if I wanted to write a book, would I be able to sell an additional 2k worth of books from attending. Here’s the quick math:

Cost: $7k

% of time I write a book: 50%

So the question = Will I receive greater than $14,000 in value

Rough profit per book (self published): $7

Amount of additional books sold needed to get my money’s worth: 2,000

After considering how many books Tim, and other people who would be attending the conference sell, I assumed the knowledge I’d pick up would probably enable me to sell 2,000+ more books than I would have had I not attended.

Keep in mind, this doesn’t even factor in all of the other things I could pick up from people at the conference. High price tag events often have many high quality attendees. It also doesn’t include potential backend sales from a book, and other opportunities I could increase my knowledge on from an event like this.

So, due to the fact I viewed this as clearly +EV, I didn’t need to go into more detailed math to make my decision.

While I still haven’t written a book, it was still a +EV decision to attend the event. If I decided to never write a book, it doesn’t change the fact that it was +EV.

—

Most entrepreneurs love Shark Tank. I know I do. Some people aren’t familiar, but the entrepreneurs give up a small % of their company (usually between 1-5%) just to be featured on the show— not including any % they might give up in a deal with the “sharks”. It’s funny to hear some entrepreneurs say they would “never go on Shark Tank because I don’t want to give away a piece of my company for nothing. I might not even get a deal!” It should be pretty obvious, but they forget to calculate in the EV from featuring their product to the millions of the people watching the show. For the majority of businesses, it’d be a no brainer to give up a % of the company for that kind of exposure. If a company was already at the point where they were pretty large, and giving up a % of the company would be worth a lot of money, that’s the point where it’d make sense to calculate the EV they thought they’d get from the exposure, and determine if it was worth it to be on. That’d also give them specific numbers to go to the producers with to negotiate a better deal. It’s hard to argue with the math.

—

One recent example for me was getting my rent renewal notice. I thought it was a bit high, and went to try to get it lowered. Some simple math versus the comps shows that I was right, and they lowered it for me.

“Hey, how can I do that!?”

I didn’t have to get this detailed to get what I wanted, but if they had declined to lower it the first time, here’s all I would have done. I would have shown them what vacancy is costing them if I move out, what fixing, cleaning and/or upgrade costs would be (they often upgrade units during vacancies) and other fees like paying a broker, versus just lowering my rate.

Example:

Rent: $2,500/month

If I move out, and the unit is vacant for just 2 weeks, it costs them $1,250.

Maybe they spend $2,000 upgrading the place.

Maybe a broker brings in the tenant they end up renting to, so they need to pay the broker.(often brokers for apartment rentals get paid 1 month rent: $2500)

So, if we don’t even include the time/money that it would cost to clean and upgrade the unit(since it would add some value), it’s still +EV for them to rent to me for a lower rate than to go through the process of needing to lease out the unit to a new tenant.

Even if it was only vacant for 2 weeks and the new renter came through a broker only 50% of the time, that’d be $2,500 extra dollars they’d need to spend, and that’s not including any of their time, or any other costs associated with the unit.

So, with 5 minutes of math, I can show them it’s +EV to keep me there at a lower price rather than trying to attempt to rent it to a new tenant.

Knowing how to calculate EV made me over $1,000 in a quick visit downstairs to the office. Most people wouldn’t have tried because they didn’t know the EV justified a lower price and gave them a great negotiating position.

Most people would attempt to negotiate rent by saying, “I’d like a lower rate.” That’s not going to help you very much. However, if you go to them and can show them how you can save THEM money, and mathematically prove it with a couple simple equations, it’s going to be a lot easier to get what you want.

—

I could go on and on with examples of all the ways you could calculate things with EV. Hopefully by now it’s obvious how easy it is to find the EV in a variety of different situations, maybe many you weren’t considering before.

Here’s something to keep in mind:

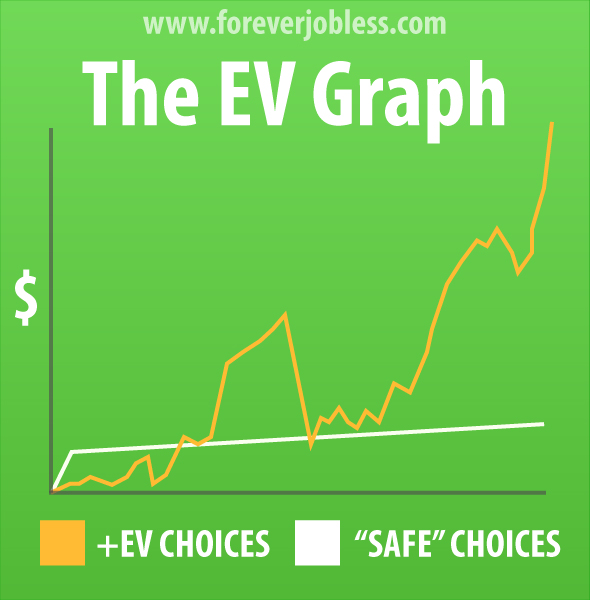

The “safe” route will often be the one that leads you toward the -EV route. Often, people are making decisions that lead them away from the +EV route because of fear of loss. In other words, they avoid “risk.” The issue is, if they attempt to completely avoid short term risk, they’re guaranteeing that their long-term risk is actually substantially higher due to them consistently making -EV decisions. Once their sample size is big enough to play out, they’re almost guaranteed not to be as successful as someone who was making +EV decisions the entire way, as opposed to making decisions that avoid short term risk.

People are so afraid of risk, that they make all of their decisions based on trying not to lose— which is often the suboptimal strategy if you goal is to win.

Many people have goals they want to accomplish, but they’re so emotionally caught up in not taking risks that they guarantee themselves NOT to hit their goals. The “risks” are actually less risky for them but they often fail to realize this because of the emotional response they have to decision making. Their emotions tell them to fear the downside, as opposed to listening to their logic which would tell them to also factor in the upside.

If you avoid risk for the sake of avoiding risk, you may also be avoiding any chance at real success. Avoiding a road that could lead to success, just to avoid risk, is how most people make their decisions.

That’s a lot riskier in my opinion.